|

Vincent van Gogh, Flowers in a Blue Vase, 1887; Kröller-Müller Museum. The various changes seen in the image below suggest that it's a modern reproduction rather than simply an edited photo, but it could be the result of digital tampering. The new version has cropped off the top and bottom of the painting, altered some of the brushwork, and taken liberties with coloring in various spots throughout. The authentic painting, which is located at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands, is shown above in the museum's photo. Recent investigation has revealed that the painting itself has lost some of its intensity, and restoration efforts are evidently underway. It isn't clear when the museum's photo was taken in relation to the deterioration of the work, so the image — although more reliable than modern reproductions — might not be entirely consistent with what might be considered the work's true appearance.

0 Comments

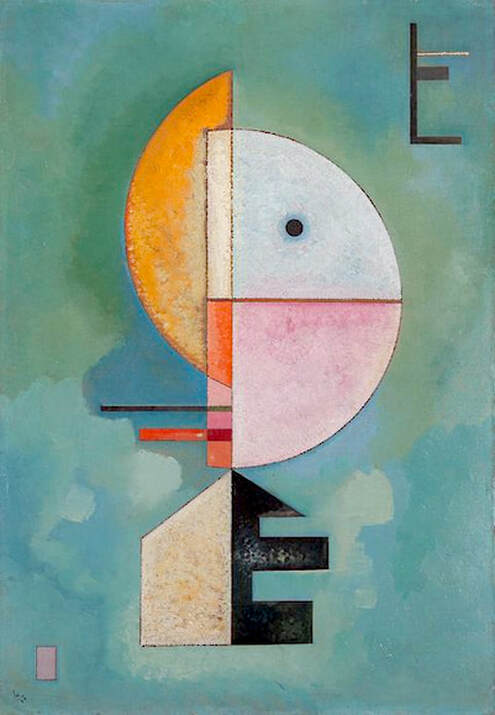

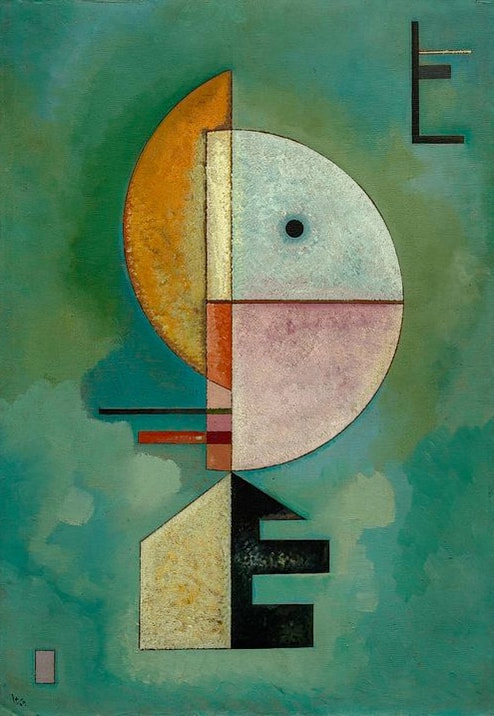

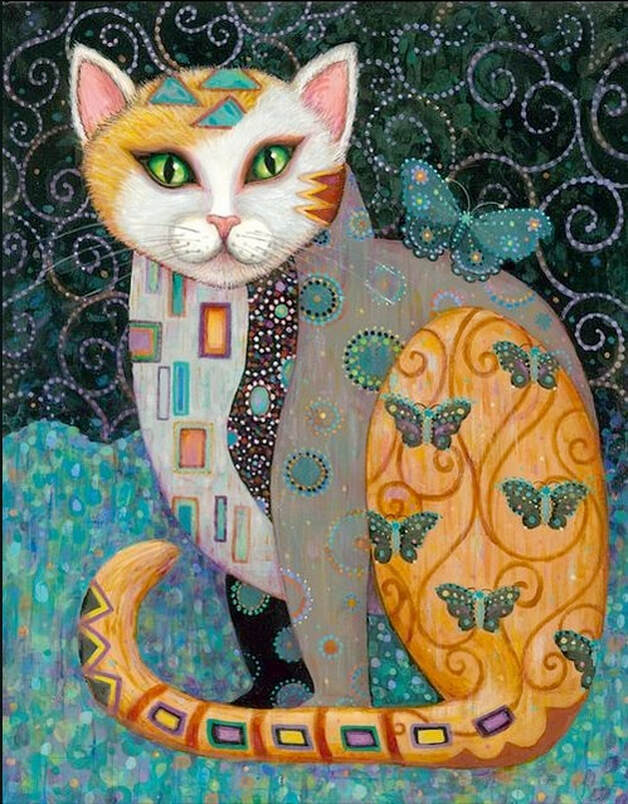

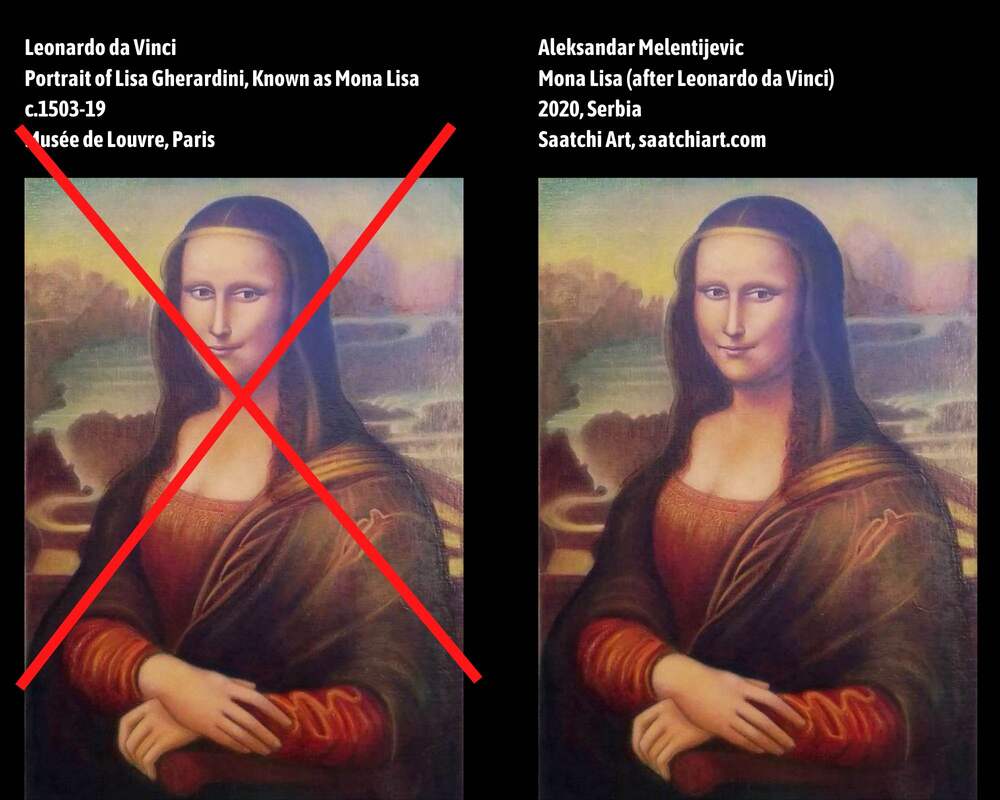

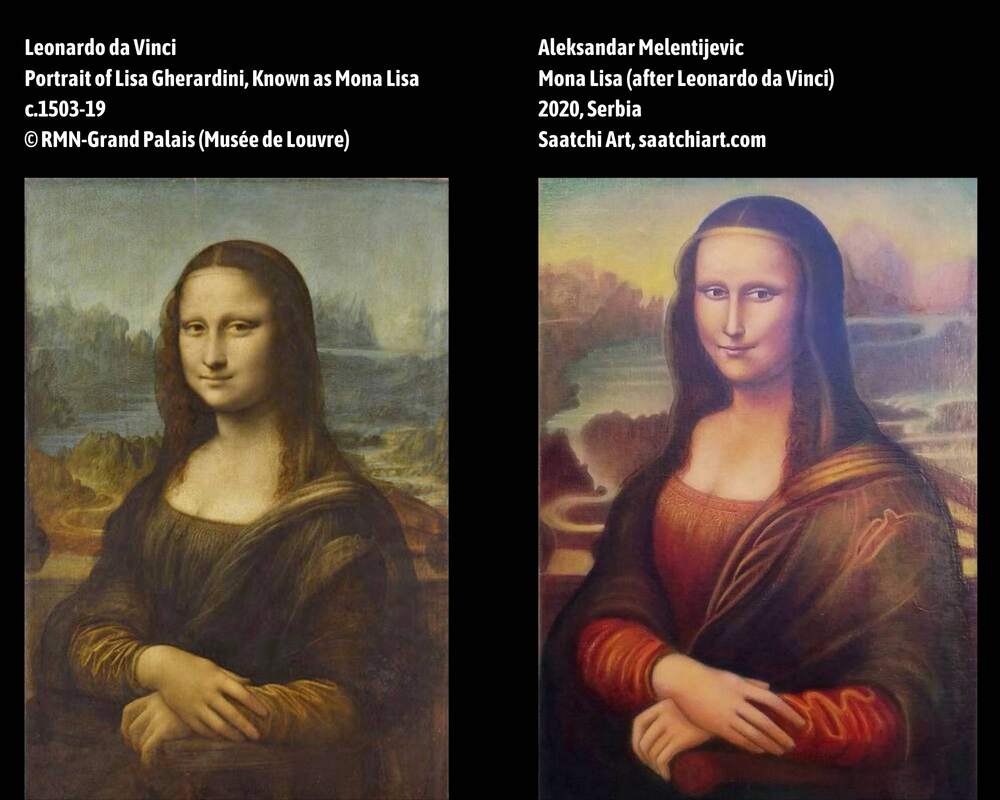

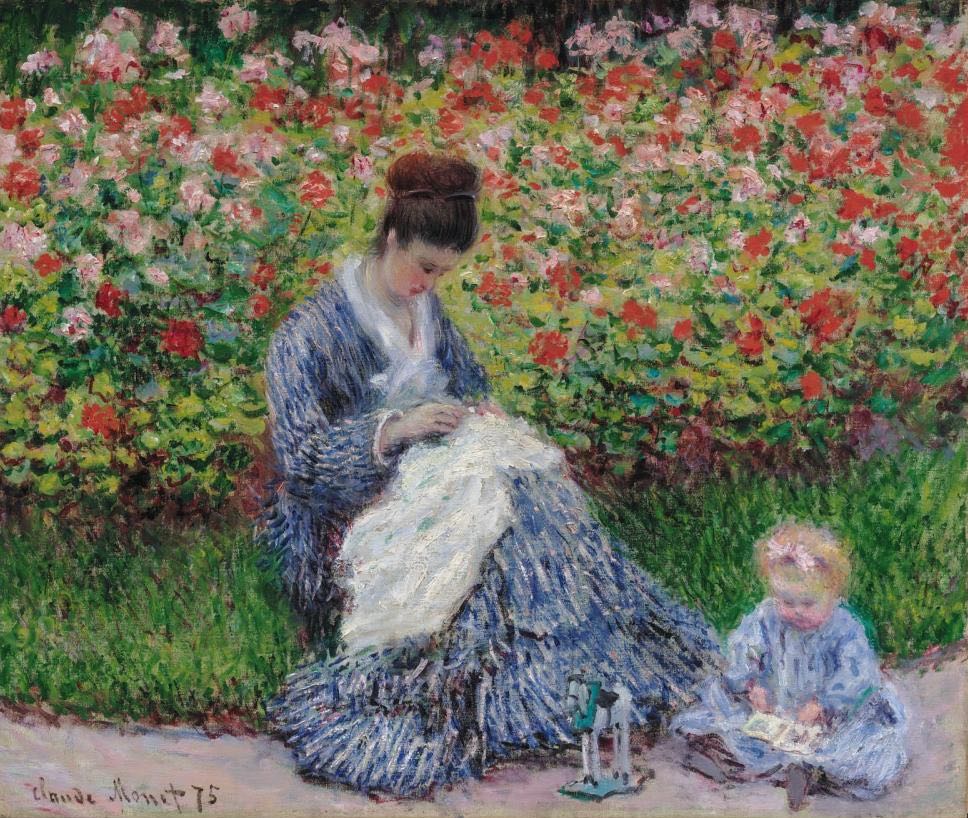

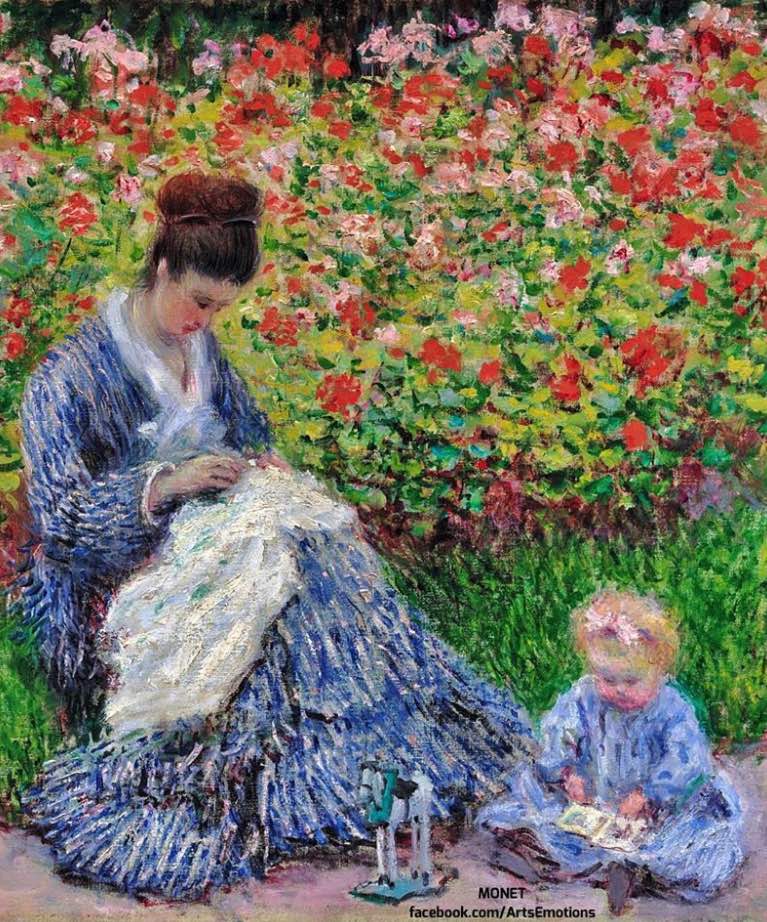

Vasily Kandinsky, Upward, 1929; © Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. There isn't a big difference here, but the altered version below does reflect changes in coloration. The work could easily be mistaken for a Klee, and collection notes mention the similarities. They also provide some additional details: A linear design in the upper right corner [...] echoes the vertical thrust of the central motif. This configuration resembles the letter E, as does the black cutout shape at the base of the central motif. These forms may at once be independent designs and playful references to the first letter of "Empor," the German title of the painting. Art has become a thriving sub-culture on social media, with thousands of copies of famous artworks constantly circulating. The problem? The lack of consistent fact-checking — by everyday users as well as top search engines. Sadly, platforms that might have educated and inspired new art lovers have instead fostered a pattern of misrepresentation and error that has undermined the integrity of authentic work. Here are some details, plus suggestions on ways to achieve a balance between availability and accuracy. The majority of fine art images found online these days are photos of commercial reproductions. Sadly, most commercial reproductions are the result of rushed, market-driven, and poorly monitored copying techniques that leave little room for accuracy. The fundamental value that society has long attributed to art is quickly being undermined by the mass marketplace, where prettiness frequently is preferred over authenticity, and where there are few protections against false claims, errors, and misleading advertising. The reproductions themselves aren't the core problem, however. The real issue is that, once an image of a reproduction becomes detached from its original sales listing — which it does almost immediately — there's no indication that it's a photo of a modern copy. Which means that it falsely presents itself as a faithful image of the original. WHAT ARE COPYISTS ACTUALLY COPYING? Reproduction houses rarely use real-world artworks as their models, and in fact, often don't even work from verified photos provided by museums, galleries, or other reliable venues. Frequently, modern copyists use photographs of other vendors' products as their models, or select random images from online searches, which are rarely reliable. Although some of these modern painters at least enlarge photos to provide more detail, that isn't always the case. In fact, videos from one reproduction company show their artist copying tiny photos from a smart phone. The accuracy of an artwork produced under those circumstances is dubious. Of course, the sale of art reproductions is a standard practice, well established over the centuries. For example, the image above is from a 1963 British Pathé film that showcases one company's pre-digital reproduction technique — a so-called "secret process" in which shop artists "over painted" stretched copies of famous artworks while imitating the original painters' typical brushstrokes. It's difficult to know how successful these artists were, but at least the company was attempting to provide the public with faithful copies — within obvious limitations — and consumers who purchased the products probably had been exposed to the originals elsewhere. In recent years, however, the Internet has permitted a previously unknown level of proliferation, without much quality control. It's common for consumers to learn about artwork from unqualified reproductions, and to associate an artist with these questionable copies rather than with the artist's authentic body of work. EVERYONE'S AN ARTIST A growing percentage of art reproductions are being created by individual entrepreneurs new to the prospering art marketplace. None of these small-scale operations are monitored in any way, and as a result, online listings often contain visual and factual errors that remain undetected by consumers. It's common for these reproductions to be sold both as newly painted canvases and as art prints, and for the images to appear on a broad range of products such as tee shirts, mugs, towels and notecards. For marketing purposes, photos of these products are usually replicated on multiple social media platforms, massively propagating any mistakes that might have crept into the modern copies. As mentioned above, attractive images might even be used by other vendors — without verification or permission — as templates for their own contemporary products. NOT A KLIMT! One of the more distressing aspects of the reproduction boom is that, occasionally, an original piece by a current artist is mistaken for the work of a famous painter, usually due to the fact that the well-known artist is mentioned in a listing as having inspired the new creation. When that happens, the contemporary piece, despite being under copyright and listed for sale at the artist's website, often gets hijacked by both mass-market art vendors and small-scale sellers. These third-party vendors then unknowingly (and illegally as it turns out) market the work using a "public domain" attribution, without notifying or compensating the true creators. Although seasoned art lovers probably aren't fooled by modern homage artwork, the general public often is, which can lead to financial and ownership issues that have few legal precedents and therefore few established remedies. THE REPRODUCTION ISN'T AT THE LOUVRE Most reproductions are captioned as though they were the originals, with the past work's creator, title, date, and current location. But that information is false. For example, the painting seen above isn't located at the Louvre. It's located at the artist's home in Serbia. Similarly, it wasn't painted by Leonardo da Vinci, doesn't date to the 16th century, and so forth. Common practice has been to assume that any information attached to an art image refers to the original painting, and that the authenticity of the photo itself — and what it actually depicts — is irrelevant. However, the lack of any further disclosure suggests that the photo is a faithful representation of the work in question. Which is rarely the case. By comparison, a factual caption that clearly describes the modern source of a particular reproduction is much more informative, and helpfully alerts viewers to the fact that, if they wish to gain true insight into a particular artist's work, they might need to look elsewhere. HOW FAR IS TOO FAR? Some modern paintings, although only loosely based on the originals, still call themselves "reproductions" and fail to mention the extreme changes that have been made to the original artwork. For example, the contemporary painting below has been seen in many places captioned as Renoir's In the Garden of the Rue Cortot, Montmartre, yet even a casual inspection reveals that the new painting has rearranged all the elements of the tall original in order to fit a shorter frame, and — as might be obvious to anyone familiar with Renoir's work — has completely altered the coloring and brushwork. A more accurate description of this new painting would be In the Garden of the Rue Cortot, inspired by Renoir. SEEING THE WHOLE PICTURE Another way that reproductions can mislead viewers is by offering a product that's a detail of the original, without indicating that the painting doesn't show the entire work. In the example below — Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist's Garden in Argenteuil, by Claude Monet, 1875, located at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston — the reproduction (possibly an art print based on the museum's photo) has used only the section immediately surrounding the two figures, in the process also chopping off the artist's signature. Since the watermark clearly indicates that it's a modern product, it might be argued that no additional disclosure needs to be made. However, online art lovers who aren't familiar with this particular painting often assume that the square version is a faithful representation, and usually don't bother to ask whether or not there's more to the original painting. HOW ABOUT MUSIC AND LITERATURE? In the visual arts, artworks are easy to alter, replicate and circulate online without encountering challenges. But the same loose interpretations wouldn't be acceptable in other types of creative pursuits. For example, suppose someone re-wrote a famous book, using the basic story line and much of the original text, but added chapters, removed sections, created new language and quotes in certain places, changed the basic personality of the main character, and so forth. And then published the book online with the original book's title, author and date — without mentioning the changes that had been made, or that they themselves had made the changes — simply presenting the work as the original. My guess is that the modern version would quickly be unmasked as a fake, and wouldn't get very far in the online universe. This sensitivity to change also permeates the classical music world, where deviations from a composer's original work are well known, spotlighted and discussed as a matter of course. Alterations to known compositions — even when considered permissible within the limits of a performer's individual interpretation — are rarely left unmentioned. Despite the lack of forgiveness in other fields, major artistic distortions are widely accepted when it comes to famous paintings. ACCURACY MATTERS Art reproductions can play a significant role in education and art appreciation by introducing newcomers to inspiring pieces from the past and by shedding light on the history that has influenced our contemporary culture. Affordable modern copies make visual art more accessible to the general public, and allow everyone to benefit from creations that are normally tucked away in distant museums and private collections. But this only holds true for reproductions that faithfully represent the original artworks on which they're based. Well-researched, expertly executed copies account for only a small percentage of artwork on the market these days. Most reproductions come from less dependable, less qualified sources. Therefore, it's a good idea to get into the habit of checking images before sharing online, and to create, though experience, a list of reliable sites that can be used both as sources and for verification. For more on finding accurate art photos, see Top Sources for Fine Art Images. Corrections or suggestions?

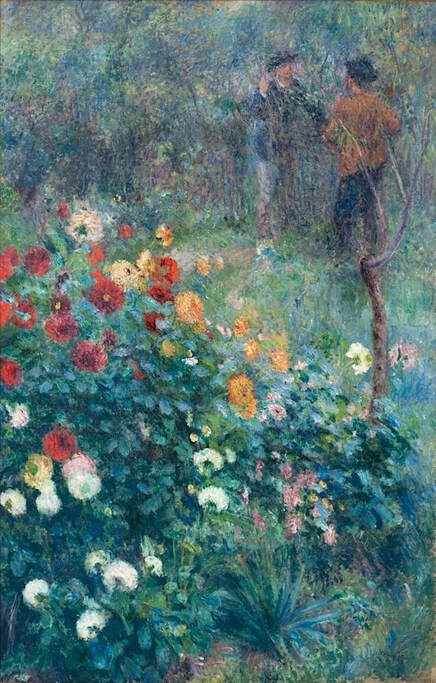

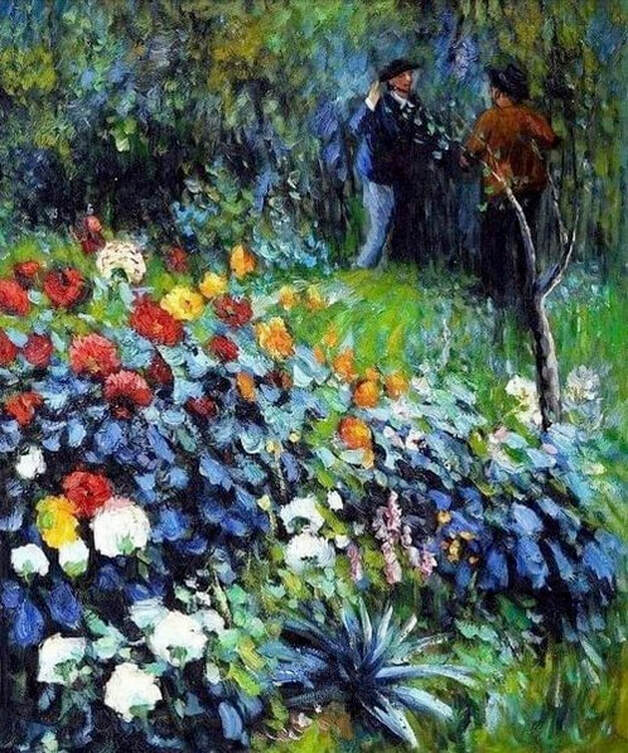

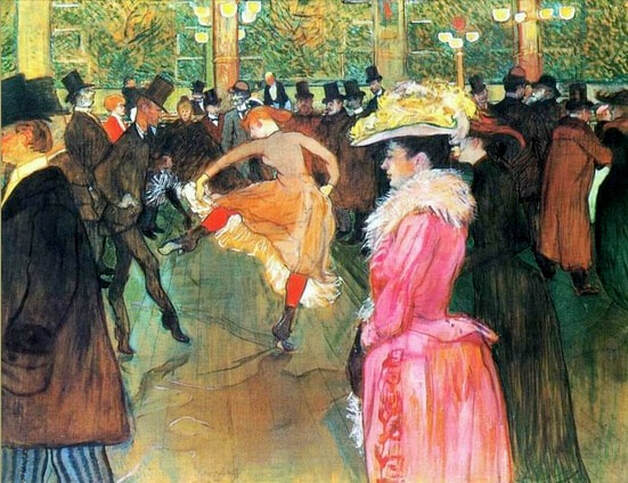

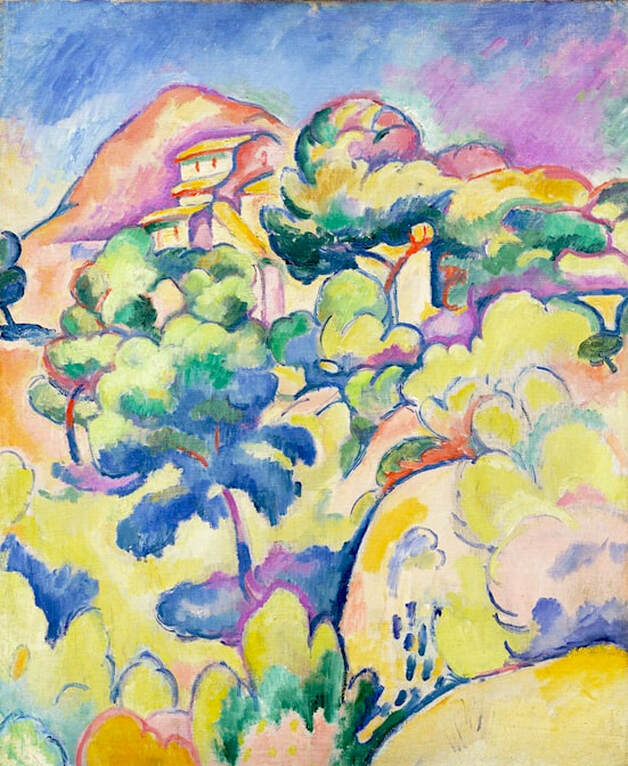

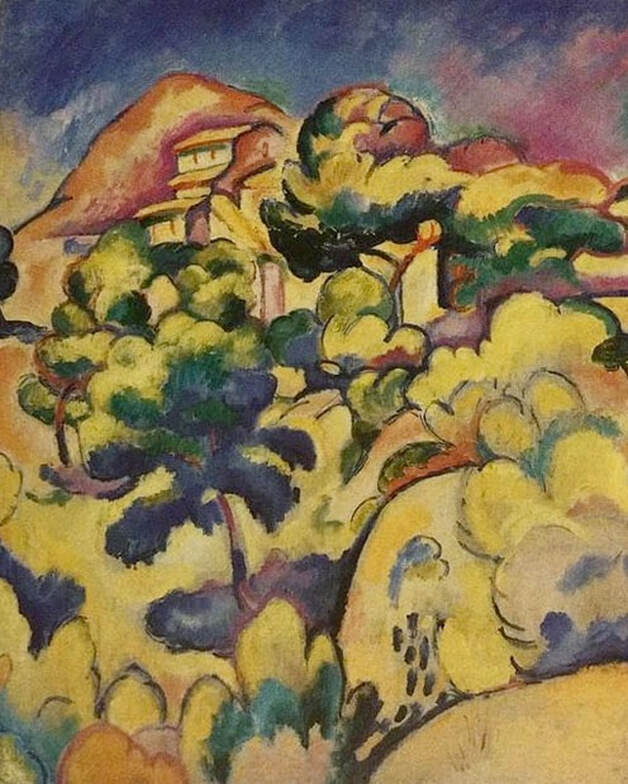

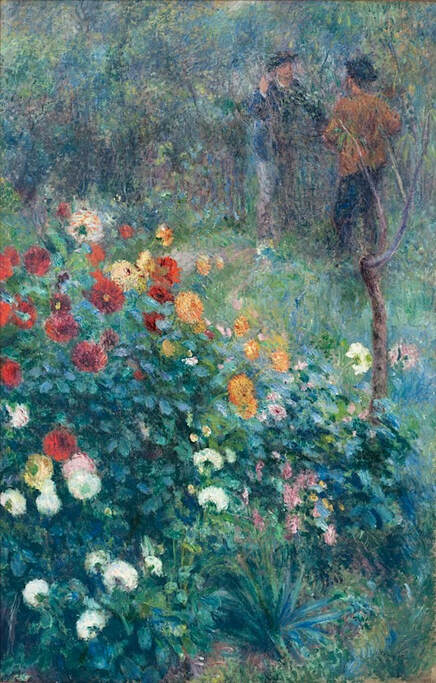

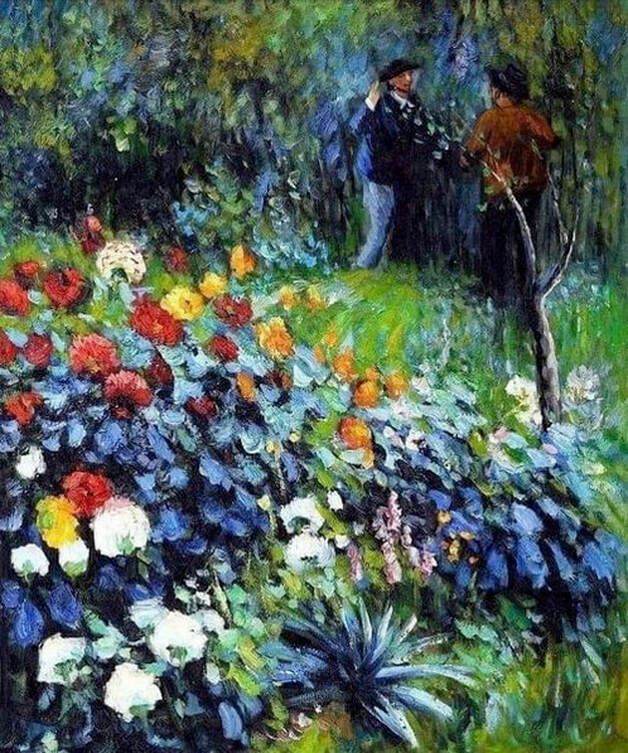

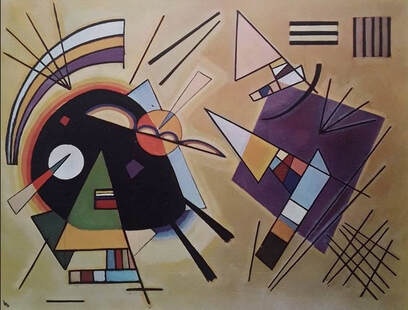

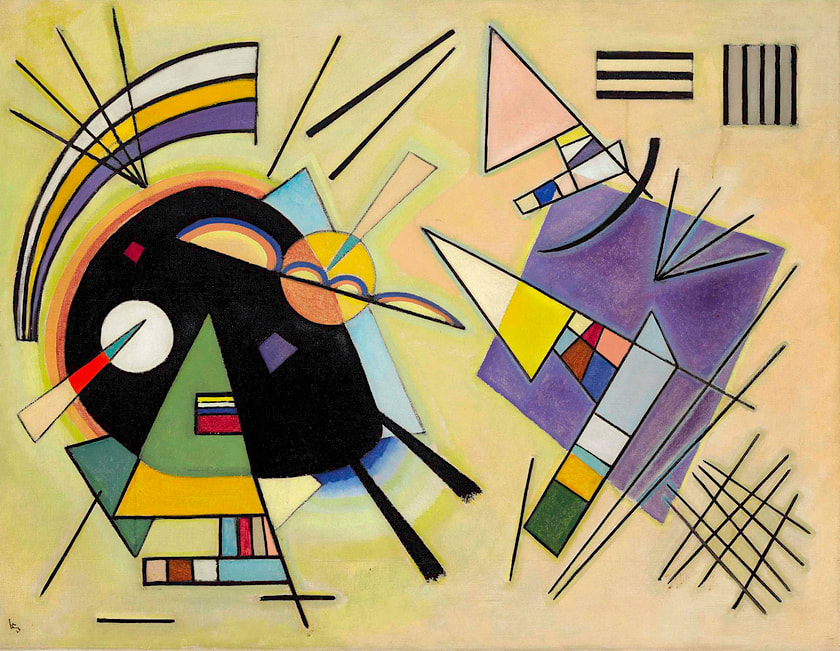

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, "At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance," c.1889-90; The Philadelphia Museum of Art. Paintings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are often brightened up and "prettified" in reproductions, when, in fact, his intention was often the opposite, to portray both the active life and the sombre realities of the demimonde. Adding color and heightening contrast also tends to damage the work's sense of space and depth, obscuring rather than enhancing the contrast that the artist meant to achieve — between the figures in the foreground and the activity going on in the background. In addition, as shown in the artificially colorized reproduction below, excess contrast frequently blots out a lot of detail. Although an original Toulouse-Lautrec might be less colorful, in most cases it's probably more realistic, and certainly more in line with the artist's highly recognizable style. Georges Braque, Landscape at La Ciotat, 1907; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. In this unusually reverse case, the oddly muted reproduction of this Braque painting looks darker and less colorful than the original. It's well known that early in his career, Braque identified with the Fauves and favored bright colors in his artwork. Landscape at La Ciotat, as seen above, is a good example. Unfortunately, the dark, brownish copy below is often seen instead, despite the fact that it barely looks like the same painting. Apart from completely altering the palette, the new version has taken the life out of the work, and obscured a lot of the interesting and lively detail. The museum notes: Before Braque met Pablo Picasso [...] he painted in the bright, bold colors shared by the Fauves. [...] They were given this name — meaning "wild beasts" — by an unsympathetic critic in 1905, as a result of the high-pitched colors and anti-naturalistic rendering they embraced. In the summer of 1907 Braque worked in the resort town of La Ciotat, near Marseilles, where he painted this landscape using heavy outlines, flattened space, and intense, harmonic colors. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Garden in the Rue Cortot, Montmartre, 1876; Carnegie Museum of Art. Although generally listed as a reproduction, the modern artwork below is only loosely based on Renoir's painting Garden in the Rue Cortot, Montmartre. The original, as seen above in the Carnegie Museum's photo, is tall in shape, and reflects Renoir's typical style, including the artist's trademark coloring, brushwork, subtlety, and depth of composition. The contemporary painting is shorter - but instead of cropping off the top and/or bottom to achieve the change, it has rearranged the composition entirely — crowding many of the elements of the original into a shorter frame. Together with the randomly enhanced coloring, the changes have produced an image that no longer looks like a Renoir. This is definitely an occasion for a so-called reproduction to be captioned more accurately as a new painting "inspired by" Renoir. Where can you find high-quality art images that accurately represent the genuine originals? Your best bet for reliable photos: museum websites. Top choice for checking authenticity: the big auction houses. Also helpful for verification: travel blogs and magazine articles. Plus, there are still a few curators on social media who supply originally sourced images and information. Whatever your goals, it's helpful to start out with the understanding that even onsite, professional photos are already one step removed from real life, and can communicate only a fraction of an artwork's real-world qualities. Digital files, in particular, can be very "lossy" on social media, and although cosmetic touch-ups can help to restore freshness, they might further skew an artwork's appearance. Total accuracy isn't achievable in the digital world; however, we can certainly do our best to track down the images that come closest. VISIT THE MUSEUM FIRST Most museums take pride in their collections and make an effort to present their pieces accurately and attractively. If you've ever tried to take a photo of a painting in a museum, you know how many variables are involved, and how difficult it is to snap a good picture. Lighting is always problematic, and color settings can be very tricky. In fact, some museums give credit to photographers in their listings, to acknowledge that this is an essential part of the curating process. Not all museums offer completely reliable photos, and not all permit adequate-size downloads. However, a large percentage of museum websites do provide excellent resources for anyone who would like to view and share artwork online. CHECK PAST AUCTIONS These days, major auction houses rely heavily on website traffic to cultivate interest and activity. Their photos must be clear, detailed, and as accurate as possible. Many art pieces that aren't in a museum have been sold at auction, which makes these websites good spots to get an inside look at authentic works that are normally hidden from public view. Most auction sites prohibit downloads for any purpose other than examination by a potential buyer, so you'll need to determine for yourself whether you're going to use these images solely for authentication, or if you plan to share them. There are so many reproductions in circulation that it's common to see several conflicting versions of an artwork in search results. In this situation, an auction photo can be very helpful. For example, here are some variations on Schwarz und Violett (Black and Violet) by Kandinsky, quickly available in a simple search. All three are probably modern reproductions. But which one (if any) looks most like the original? It's hard to tell just by looking at them. Luckily, there's a good photo at Christie's, where the authentic work sold in November 2013, incidentally fetching a price of $12, 597,000. Schwarz und Violett, Wassily Kandinsky, 1923, © Christie's Note that it's important to differentiate between real-world auction houses — those that have a street address, a long history and excellent "credentials" — and online auction websites that might or might not present reliable images. Some simply report on auctions held elsewhere, while others are in the business of auctioning newly created reproductions. And there are some that auction a variety of art-related items, from vintage to newly minted. A bit of trial and error might be necessary to pin down a particular site's dependability. What about large, diversified marketplaces like eBay, Etsy and Fine Art America? That's a topic in itself and will be discussed in a later conversation. BROWSE ONLINE PUBLICATIONS Well-known magazines and newspapers that cover arts news can also be good sources for art images. Many feature local exhibitions and museum shows, as well as auction highlights, and updates about issues of interest to the arts community. Most of these articles contain location shots that can help with authentication. They also might include closeups taken by staff professionals, or full-frame images purchased from image archiving services. The copyright and download restrictions for these publications vary, so check before reposting. Note that images in online publications aren't always reliable. Some sites simply grab photos via search, and therefore occasionally repost others' errors. A little experimenting might be necessary to determine the reliability of a particular news outlet. Also keep in mind that some online art "magazines" are really just personal websites that collect art images and post them in a publication format, without necessarily checking their accuracy. Some even add information taken from user-driven sites like Wiki, also without verification. CONSIDER THE BLOG UNIVERSE Personal blogs that happen to include art images are difficult to find on purpose, but they sometimes turn up in a general search. They're worth investigating, because they often contain in-person photos that be used for authentication. There are also travel blogs, museum blogs, and assorted blogs about history, art, culture, architecture, and so on, that might contain high-quality shots taken by professional photographers. Copyright restrictions might apply, so check use notices before sharing. A WORD ABOUT ART GALLERIES Most professional art galleries focus on modern and contemporary artwork still under copyright, which means image use is often restricted. There are also some high-end art dealers that include or specialize in artwork from earlier periods, with similar limitations. However, art galleries can help with authentication, often include blogs, videos, background articles and other informational materials, and some do permit personal or educational use of their photos. In addition to these professional galleries, there are many amateur sites that collect images and information from other locations, and aren't connected with real-world art organizations or institutions. In fact, many are actually storefronts for companies selling art reproductions. Note that a site with an artist's name in its title isn't necessarily an authorized source of information or images. It's probably best to confirm accuracy before relying on unofficial sites of this type. David Teniers the Younger, The Archduke Leopold William in His Picture Gallery in Brussels, 1647-51; Museo del Prado. CAN SOCIAL MEDIA BE TRUSTED? We'll go into this subject in more detail at a later date, but in the meantime, remember that about 90% of the art images you see on social media have been shared from other locations without verification. Most are commercial reproductions, and unfortunately most online art vendors don't produce exact or even close copies. Although we tend to assume that art pages and accounts — those devoted exclusively to art, for art lovers — carefully research the images and information they publish, that isn't always the case. Note that works by current artists, posted by the authors themselves, fall into a different category. Presumably, those photos are accurate, but copyright restrictions usually apply. Summary: Use caution when sharing from a social media account. To be certain, check any sources listed. Corrections or suggestions?

|

REAL or REPRO?

A well-researched art resource that can help you find accurate images and spot altered copies. 100+ listings and growing daily. Browse at random, or search for something specific. Special requests are welcome.

Categories

All

Archives

January 2021

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for entertainment purposes only. Although every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information provided, the material included here should in no way be considered the final authority on any issues discussed in the text.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed